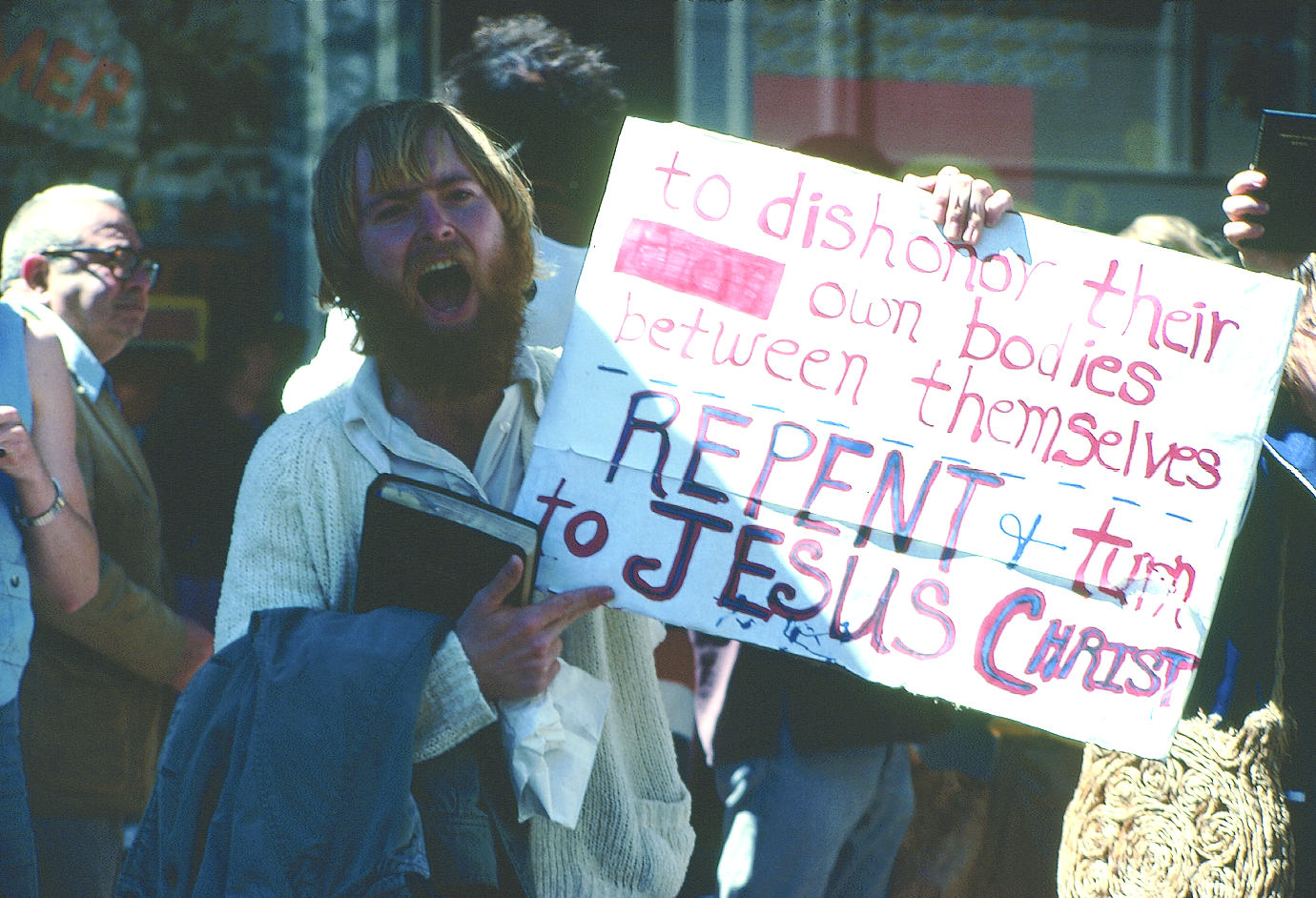

As moderate as a parade and picnic may appear, the participants performed an impressive act of rebellion by openly declaring their sexuality in the midst of extreme hostility from American society.

—Leo Laurence describing the arrival of equestrian officers from the San Francisco Police Department at the June 28 Gay-In that attracted some 200 people to Speedway Meadows in Golden Gate Park. Police detained several of the participants. Source: Berkeley Barb (July 3–July 9, 1970).

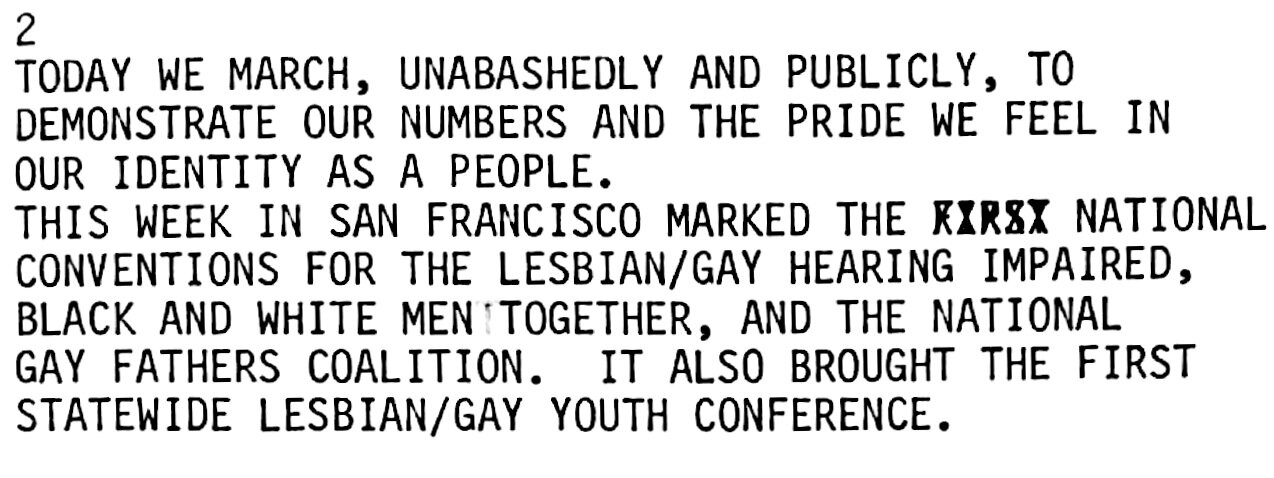

No formal statement was issued that first year, but one activist made clear the purpose of the “beautiful and peaceful” event: In the face of oppression, “homophiles gathered in pride in their identity.”

A participant in the 1973 Gay Freedom Day Parade discusses what and who the parade is for and why it matters.

The organizers’ interpretations of how to demonstrate those goals by guiding an ever-growing Gay Freedom Day Parade and Festival would vary greatly. Individuals and groups joining in as participants or spectators also would bring their own perspectives on the purposes of the event and its effectiveness as a movement tactic.

—The Rev. Robert Humphries (1934–2002) sums up the value and importance of the Gay Freedom Day Parade 10 years after it was launched. Humphries had helped organize the 1970 and 1971 parades in Los Angeles and had served as committee chair for the 1972 parade in San Francisco.

Hundreds of individuals volunteered countless hours, weathered frequent criticism, made not a few mistakes, and managed to lay the foundations for San Francisco’s massive annual Pride celebrations of today.

By the time Milk became California’s first openly gay elected official as a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1978, mainstream media were increasingly providing advance coverage of the event—and that same year, the Parade Committee obtained its first grant from the city.

“The Gay Freedom Day Committee should get funds equal in proportion to the turn-out of the other parades. The ‘gay’ oriented hotels should withhold their tax dollars until this happens. The Gay Day Committee should sue if it does not get its fair share.” —Harvey Milk, “Political Views: Milk Forum,” Bay Area Reporter (July 10, 1975)

Both the documents and the gatherings reflect the extensive behind-the-scenes work required of committee members and volunteers putting in countless hours to make the parade a reality and to represent the diversity of the community.

One such project was the creation of the rainbow flag by Gilbert Baker (1951-2017) and a group of volunteers. Now an international symbol of LGBTQ community, the flag debuted with two examples flown on the monumental flagpoles at United Nations Plaza on Gay Freedom Day, June 25, 1978.

The archives of the GLBT Historical Society preserve artifacts, photographs and historic documents that nonetheless give us a glimpse behind the scenes at the dauntless efforts that were required to keep Pride marching through its first 10 years.

Perennial favorites: t-shirts and buttons. Wearing them signaled participation in an emblematic public statement of Pride. They also gave wearers a way to declare their belonging to a social group: “I joined thousands of people in the streets of San Francisco to celebrate our community.”

Debates about respectability, commercialization, protesting versus partying, and the place of women, drag queens and people of color became inextricably entwined in the implementation of Pride during its first decade. Power struggles, heated exchanges and hurt feelings were perhaps inevitable. The organizers were passionate people navigating their own experiences of trauma and marginalization even as they put together an enormous public gathering that sought to reflect a vastly diverse community.

George Mendenhall, the editor of Vector, the magazine of the Society of Individual Rights, published an editorial in 1972 casting doubt on the value and organizational integrity of what he called the “Gay Parade.” In response, a self-proclaimed “Vectorious Truth Committee” pushed back in a satirical flyer accusing him and SIR of spreading “lies.”

Emmaus House, a “gay switchboard” and service organization, sued the Christopher Street West Parade Committee for $200 in small claims court, claiming that the proceeds from the year’s event had not been distributed to the city’s gay social-service organizations as promised by the committee.

These fights shed light on the profound importance of Pride as a means of proclaiming and promoting gay liberation.

Gay Freedom Week chair Steve Ginsburg quashed rumors about an irreparable rift in the Gay Freedom Day organizing committee, whose members asserted that the San Francisco parade would be “the largest and only one in the West.” At the same time, another organization, the Gay Activist Alliance, headed by the Rev. Raymond Broshears, was in fact planning a competing celebration in the Civic Center.

After two years serving as the chair of Gay Freedom Day, Steve Ginsburg had reached his limit serving in this leadership role. Resigning in 1974, he declared that the gay community in San Francisco was “royally and alcoholically fucked.”

The San Francisco Gay Liberation Alliance protested the participation of the Imperial Court, a charitable organization of drag performers, in that year’s Gay Freedom Day Parade. GLA decorated a vehicle with representations of “dead” drag royalty, asserting that the Imperial Court was “a poor representation of the gay community and a waste of monies.”

A coalition of organizations including the Gay Latino Alliance, Gay American Indians, Bay Black Caucus and Lesbian Action Organization voted a resolution declaring that the Gay Freedom Day Parade had lost sight of the true meaning of the 1969 Stonewall riots.

The resolution characterized Stonewall as a moment during which “Third World Gays, Lesbians, transsexuals, and transvestites rose up as one and shouted ‘I’m here’ to the fascist forces of oppression.”

Liane Esstelle, calling herself the “token woman” on the Gay Freedom Day Committee, declared in an open letter to the community that she refused to be pushed around, “not even by a queen.” She accused the committee chair of having “sexist, racist and anti-human attitudes” in this document. Esstelle inscribed a copy of her letter to Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, two of the cofounders of the lesbian organization the Daughters of Bilitis.

The informal anarchist group Anarchist Flashers protested the Parade Committee’s attempt to ban nudity — but also noted that women whose bodies have been “abused and manipulated” may choose to dress rather than undress. Members declared that “the human body is not the problem” and that sexual repression only distracts us from more pressing issues of imperialism, capitalism, patriarchy and white supremacy.

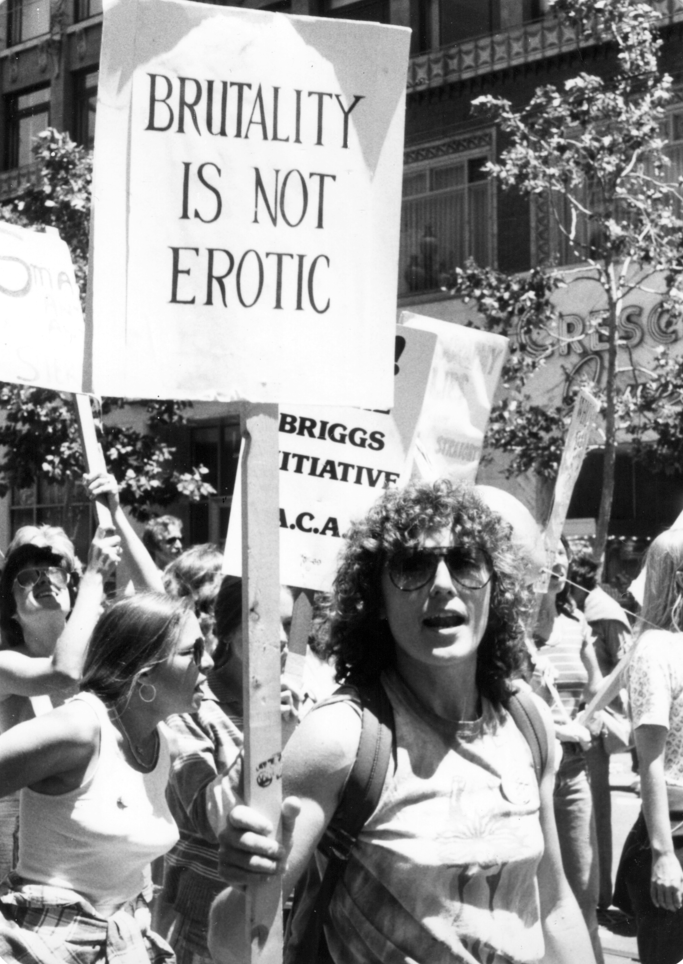

The Gay Underground Theater protested the Bay Area Committee Against the Briggs Initiative’s efforts to turn the Gay Freedom Day Parade into a political march and rally. The Committee was working against the Briggs Initiative, a state ballot measure put to the voters in November that would have banned gays and lesbians and their supporters from working in California public schools.

The satirical flyer on the right opposes the fictional “Larry Rice” of “Gays Opposing Discrimination” (GOD) who urges parade-goers to wear gray business suits so that gay people will “appear as socially acceptable members of the bourgeoisie.” Actual calls for dressing and behaving in conventionally respectable ways at the parade were a recurring phenomenon — and were met with anti-assimilationist responses, such as this example of sublime queer sarcasm.

Disgruntled members of the LGBTQ community campaigned against the move of the Pride “corporate board” to eliminate general membership and community involvement in direct decision-making about the Gay Freedom Day and Parade.

A month later, the newly incorporated Lesbian/Gay Parade Committee, pushing for equal representation, replaced the Gay Freedom Day Committee and drafted bylaws to preserve “grassroots control” of the parade.

During its planning for the 1980 parade, the Gay Freedom Day Committee proposed resolving disputes about who should address the crowd at Civic Center by doing away with all speakers. In response, the Stonewall Coalition of radical activists, women and people of color declared, “We are concerned about the conscious attempt to de-politicize the march, particularly by eliminating the speakers’ program and creating a carnival atmosphere.” The coalition’s flyer calling for a protest at the committee meeting featured a photo of Harvey Milk with his mouth taped shut.

Committee leaders, members and volunteers stepped up to the challenge knowing full well that getting involved meant facing criticism.

What remains remarkable is how, even as it endured perennial dangers of internal division and external attack, Gay Freedom Day continued to grow into the huge event that we know as San Francisco Pride today.

2. Interviews with Sue Davis and Robert “Smitty” Smith, hosted by Randy Alfred, February 11, 1979.

3. MC Robin Tyler and speaker Barbara Cameron at 1981 Gay Freedom Day Celebration in Civic Center, aired on July 5, 1981.

From the early years, individuals and groups used Gay Freedom Day to express sameness and difference. To do this, they crafted signs, unfurled banners, recruited contingents, drafted speeches, constructed floats, detailed motorcycles, sewed sequins and donned outfits—or stripped down.

Throughout the years, political, cultural, racial, gendered, sexual and economic differences often frustrated efforts at unity, solidarity and coalition.

Despite the challenges, Gay Freedom Day sought to gather everyone into collective identity, visibility, pride and political empowerment, asserting that—as the 1976 celebration’s theme would attest—“Our Diversity Is Our Strength.”

Quoting from the San Francisco Chronicle, June 26, 1972, "Their Jewish Gay Liberation contingent carried signs proclaiming 'Chutzpah' (gutsiness) and sang a Hebrew folk song, 'Have Nagilah.'"

Bursting out every June as the annual reunion of one big gay, dysfunctional family, Gay Freedom Day showcased fierce, funky and fun ways of belonging in the world.

Coming together in this way presented a dazzling alternative to the straight and cisgender social order.

Many of the forces that emerged in the first 10 years have continued to shape Pride:

Today, San Francisco Pride may appear institutional and inevitable: a convergence of organizations, elected officials, corporations and individuals into a massive civic event and public party. In what ways do you think the event has become a means for advocating positive social change?

Considering the turbulent first decade of this complex annual gathering, and how for the first time in its 50 year history, San Francisco Pride was canceled in 2020 in response to the coronavirus pandemic:

• What do you want SF Pride to look like in the future?

The curators wish to thank the following for their assistance with research for the exhibition: Blackberri, Paul Gabriel, Carly King, John Raines and Marc Stein. And thanks especially to all the people who created, fought over, resisted and demanded more out of Gay Freedom Day in its first decade. Their efforts made a priceless contribution to our community's legacy of struggle, celebration, strength and resilience.

This exhibition is made possible in part by First Republic Bank. Additional support for Labor of Love: The Birth of San Francisco Pride 1970–1980 is provided by San Francisco Pride.

Leigh Pfeffer, Manager of Museum Experience, Public Programs

Jeff Raby, Graphic Design, Creatis Group, Inc.

Mark Sawchuk, Ph.D., Communications Manager, Editor

Ramón Silvestre, Ph.D., Museum Registrar and Curatorial Specialist

Contact, GLBT Historical Society

Copyright © 2020 The GLBT Historical Society; all rights reserved.

The contents of this exhibition may not be reproduced in whole or part without written permission.

![Marcher holding a sign that reads “Marajuana [sic] Is God’s Gift. So Are Breasts,” Gay Freedom Day Parade, 1978; photograph by Robert Pruzan, Robert Pruzan Collection (1998-36), GLBT Historical Society.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b53b13285ede173115cb784/1591836904242-VNE0TSV47M8AANMEYTLI/breasts.png)